CHAPTER 3

Performance based

reflections

on

Irish-Indian musical sympathies

Practise based reflections

So far, this thesis has explored the issues of hybridity and Irish-Indian musical sympathies through a survey of relevant literature. However, the main argument of the preceding two chapters has been to vindicate a practice and performance based response rather than a predominantly literary one, to these issues. This research has already explored the limitations of a discursive and abstract theoretical approach to understanding musical hybridity in general. While drawing upon more traditional ethnomusicological scholarship, the following chapter is primarily informed by an arts practice research model where the individual interrogates their own artistic practice as site of experience and as a means of generating new knowledge. As outlined in the introduction, over the course of four years of this research, I have been using my own practice as a sarode player to explore the performance possibilities of Irish traditional and North Indian music. At the same time, my practice is an exploration of hybridity beyond the boundaries of Irish or Indian music and is representative of my own quest for an authentic musical self, which I understand through the metaphor of the mongrel.

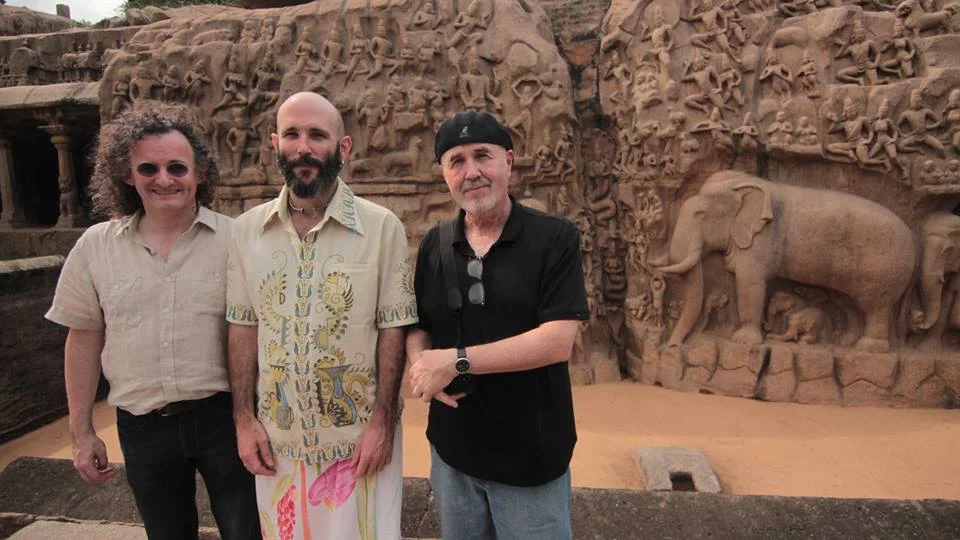

As well as learning Irish material in traditional manner, I have also taught Indian music to ensembles of traditional music undergraduate students. In these ensembles, we explored the possibilities of improvisation with Irish tunes using the basic principles of North Indian classical music.[1] Concurrently, through my engagement with my own “critical meta-practice” (Melrose, 2002), I began to unravel the multiple threads of my artistic narrative and attempt to integrate these into my playing on the sarode.[2] Following on from the ensemble work with students in the Irish World Academy, I decided that it would be crucial to work with a smaller group of musicians to generate a major performance piece. To this end I was lucky enough to establish a musical relationship with renowned fiddle player Martin Hayes which resulted in an ongoing collaboration and a 2 week tour of India.[3] This tour, its surrounding discourse and my own reflexive experience are the focus of this chapter.

The mongrel in India

Martin Hayes and Dennis Cahill are perhaps the most celebrated contemporary duo in Irish traditional music. Martin is an All-Ireland champion fiddle player and son of the legendary P. Joe Hayes who was a founding member of the great Tulla Ceílí band. He learnt primarily from his father but was also greatly influenced by an older generation of musicians from Co. Clare including Paddy Canny, Martin Rochford, Junior Crehan and the renegade genius of Tommy Potts.[4] He relocated to the U.S. as a young man and was exposed to a wide variety of music but has always maintained links the Irish traditional canon and was awarded the prestigious Gradam Ceol in 2008. It was in Chicago that Martin met his main collaborator for the last 25 years, guitarist Dennis Cahill. Cahill came primarily from a jazz background but with his minimalist and subtle aesthetic, is now regarded as one of the most innovative accompanists on the traditional music scene. As a duo, their approach to traditional music is stripped down and follows carefully constructed dynamic arcs in which several suites of tunes are intertwined to produce a musical gestalt. They have performed in major venues all across the globe, have released several successful albums and recently have been fundamental in the success of the Irish 'super group' the Gloaming.[5]

When I first heard Martin Hayes and Dennis Cahill it was on a cassette. I had just settled in Ireland after years of sojourns to Kolkata to study Indian Classical music, and for me it was the first time I ever really appreciated Irish music. As I listened to the long passages of melodies which spiral upwards in ever increasing tempo and dynamic, I felt an affinity with the music because it reminded me of raga. For me, the slow airs worked like an alap (the melodic introduction of Indian Classical music) and then evolved slowly in tempo to the passionate abandon of reels, much like the dynamic arc of a typical Hindustani performance. The album was Live in Seattle, and I soon discovered that I wasn't the only one who heard this similarity to Indian music. One reviewer described his experience listening to the album, “I was reminded of the rapport which builds up between pairs of virtuoso Indian musicians...a sitar and tabla performance, where the tabla acts as a supporting voice to the main instrument, and occasionally breaks out into solo extemporisations” (Mc Cormick, 1999).

Several years later I was lucky enough to meet Martin Hayes and discovered that we were living a few miles apart in East Clare and had a mutual interest in Indian music. I was fascinated to hear that Martin had a love for Indian classical music and had listened extensively to Sth. Indian violin maestro, L. Subramaniam.

I would claim, in my own small way, to have been influenced by Indian music in the way that I construct medleys of music and the kind of trajectory and energy of them. I was quite taken by Indian music when I first heard it. I was also influenced deeply by the intentionality and the purposefulness of it and the obvious soulfulness and spiritual nature of the music. That has left a big mark on me (in interview, 2015).

Through my contacts in India, I proposed to Martin the idea of organising a small tour across India, in particular for him to meet L. Subramaniam, and also to engage more deeply with the Indian classical tradition. Eventually, in December 2014, thanks to Culture Ireland and the Irish embassy, the idea became a reality and I accompanied Martin Hayes and Dennis Cahill on their first ever tour of the Indian sub-continent. The concert formats featured Martin and Dennis as a duo, with myself joining them as a guest for several pieces, culminating in larger collaborations with local musicians. Performances were scheduled in large auditoriums and also much smaller halls and musical institutes in New Delhi, Bangalore, Chennai and Mumbai. The following ethnography will focus particularly on my own practice within the context of the collaborations as well as examining more detail of the performances and interactions in Chennai with veena player Karaikuddi Subramanian. Some reference will be made to performances from the whole tour but for a more thorough impression please watch the documentary which accompanies this text, The Sound of a Country by Myles O' Reilly.[6]

The 'tour'

In a nutshell, the tour was a success. Critics and audiences were blown away by the heartfelt musicality of Martin and Dennis as a duo and responded positively and with great curiosity to my own approach to Irish music on the sarode. The larger collaborations, with piano, bansuri and tabla in Delhi/ Mumbai and with veena and mridangam in Chennai received positive reviews, national media coverage and standing ovations from audiences. The documentary about the tour continues to receive a wide audience online.[7] Our funders were all happy with the cultural exposure we had provided for Ireland. Indeed, the project became something of a poster child for Culture Ireland's success in cultural diplomacy and the film featured on their website and subsequent public events.

Yet the reality of the tour is much more complex. While the concerts may look and sound great and it seems like we are all having the time of our lives, which we usually were, the tour was also a large scale production dictated by factors of commerce and fraught with logistical difficulties. This element is not documented in the film and general media coverage of the events. While I agree that music is a social production (Merriam, 1964), it also is increasingly a commercial production. Before we even boarded our planes for India, there had been almost two years of planning and negotiating between dozens of promoters and organisations. Ironically, the amount of thought and time given to planning and administrating the tour far exceeded the amount of time given to the actual music making.

In this way, the tour could be understood to exist as its own entity before we arrived. Even before we started rehearsing the music, we would talk about 'the tour' as an actor itself in our collaboration. In this regard, 'the tour' is a character in this story as much as the actual musicians and the performances. For 'the tour' has demands. 'The tour' does not allow for slow organic interaction between musicians. The collaborations needs to put bums on seats to satisfy sponsors and promoters. The shape of ‘the tour’ is constructed months before the musicians even met. Therefore, the music has to be made to work in a short space of time. Rehearsals are timetabled just days and even hours before the already advertised event. Venues have been booked, sound and lighting paid for and tickets bought. Ultimately, 'the tour' has high expectations of its participants. The tour as a character, perhaps more than any single individual, deeply impacted on how we could make music and therefore placed certain constraints in which to pursue my research questions. The demands of the 'tour' restricted the extent to which I could pursue the sympathies between Irish and Indian music. It existed as a constant background character in the examination of my own practice and what makes these collaborations work. The way 'the tour' has been marketed and documented in the media, also reflects important perceptions of Indian and Irish culture and the ways in which music can be both a cultural and commercial commodity. The way the tour was 'born' also highlights the complexity of the relationship between the commercial and cultural exchanges of these performances and the important role of my own mongrelity as a mediating agent in these interactions.

A mongrel in the henhouse

There were several promoters on the ground in several cities in India trying to book dates for, Martin and Dennis as duo, the three of us as a trio, as well as and further collaborations with Indian artists. All of this communication took place via hundreds of emails while Aine Edwards, a Cork business consultant who is now based in Chennai, focussed on networking to procure further funds and/or corporate sponsorship for Chennai performances and the tour in general. However, we initially had a great deal of trouble booking dates in the National Centre for Performing Arts in Mumbai, which is a renowned Indian Classical venue. Partly, this was due to availability of dates and the slow communication channels between Indian bookers, myself and Aine. Interestingly, there was also some difficulty in promoting my own involvement with Martin and Dennis as a trio. Bookers were asking for images or video of the three of us (which didn't exist) and there was some discussion of the conservative nature of Indian audiences. Below is an email conversation with an Indian Classical promoter from Pune/Mumbai.

Dear Mattu,

I would also like one clarification at this stage. Will you be performing with the duo on the sarod for the proposed concert? Or are you only joining them for the recording project? Are there clips of you and them playing together which I could show my colleagues in Mumbai? Can you also give us an idea of the proposed programme?

I must warn you that in Mumbai they generally tend to present straight-laced stuff.

Look forward to your reply.

Very best, J.

Although the tour was originally to be billed as a trio, it soon became clear that as a professional level tour, which was seeking significant funding from within India, it made more sense to market the event as Martin & Dennis plus myself and other Indian musicians as guests. My mongrelity, in this respect, was a hindrance. I was neither Indian Classical or Irish traditional and an Australian just to confuse matters more. In terms of marketing and promoting the project to bookers, I was betwixt and between categories. Ironically, I was the exotic, the odd one out. Not only was I an exotic but I was perhaps a slightly threatening unknown- like a mongrel dog that might get in the henhouse and destroy all the hens. This difficulty was compounded by the fact that we did not have the required promotional material as a trio such as hi-res photos, recordings or YouTube clips. You can see in the initial image design for the tour that we had to be photo-shopped together, and not too successfully either. Despite our collective musical abilities, we could not book shows as a trio. While subsequent promoters, Pancham Nishad and Arts Interactions in Delhi & Mumbai, TommyJamms in Bangalore and Aine Edwards Consultancy in Chennai, did not voice concerns such as those in the quoted email, there was a clear emphasis on Martin & Dennis as the traditional duo with myself to be added as a guest when was appropriate. It was also suggested early on that I take out my own reference to the mongrel in some of my biography and research descriptions.

Once the general vision of the tour had been agreed upon, there were daily email threads with questions to be answered about the details of format of the concert, bios to be re-written, new stage plans to be devised and financial and logistical questions to be covered. I worked closely with Arts Interactions and Aine Edwards Consultancy to devise a biography and press release which captured the tour. The promoters were adamant that a live photo be included for the main tour image and a great deal of time was spent trying to source something of hi-resolution quality. The management firm Arts Interactions, who have experience with both Indian classical and fusion concerts, suggested that Indian audiences would need to be sold the virtuosity and high profile of Martin and Dennis. As Martin and Dennis are almost completely unknown in India, as is Irish music in general, the tour's media image was geared towards catching the attention of classical audiences through dynamic images, striking quotes and energetic video clips of high profile live performances.[8]

The slow and mournful airs and gradual builds were not part of the marketing. Also, there was a great deal of attention to name dropping famous venues and people. In the biography, special mention is given to citing performances in America, Japan and in Australia at the Sydney Opera House and a quote from the Sydney Morning herald is given as the main review, ‘one of the wonders of the musical world...transcendentally beautiful playing’. The promoters were also constantly asking me for more information to put in the biography about high profile names they had performed for. Although only anecdotal and not part of Martin and Dennis's official biography, reference was made to their performances for President Barrack Obama and Paul Simon as it was felt that these were household names amongst the middle class Indian audiences we were trying to attract. Despite my discomfort in doing this, the promoters felt it was necessary to establish their international credibility to the 'new market' as relying on the music alone would not be enough. Focus was given to the quality of their musicianship, “beautifully etched playing” and also something of the somewhat spiritual or efficacious nature of their music which, “involves the audience and transports them into spirited atonement”(from press release). Some of this material was already in the Martin and Dennis bio, but from my own explicit aim of wanting to reach a classical audience and the local promoter’s interpretation of how best to do this, this particular approach to highlighting virtuosity and spirituality was taken.

Furthermore, an attempt was made to bridge the cultural gap through an explanation of my research topic. Without any of my own prompting or suggestions of material, the promoters did some cursory research into Irish-Indian links and paraphrased this notion as the opening section of the press release.

Comparison of European Celtic Culture with Hindu Culture shows large similarities between them. Language and words share Sanskrit roots. One of the world's great musical duets is touring Indian in December- from Ireland's Celtic Culture...The tour is an important part of research. Mattu is researching the links between Indian and Irish music. What are these links? It is hoped to find out more about these in India in December” (press release).

My contribution as a guest artist was attributed to a sort of mix between the two cultures combining the rhythmic drive of Irish music with the transcendental mood of Indian classical music, “joining them on tour is Sarod player, Mattu Noone, who adds to the irresistible rhythm of Irish music taking the audiences on an ecstatic musical journey” (Press release).

The water of life and the ‘gurus’ of Irish folk scene

Sponsorship was a significant element in getting the tour moving. Apart from Culture Ireland, the Irish embassy in Delhi supported the tour as well as multi-national company, Picard Richard who own Jameson Whiskey. This sponsorship was significant in its financial input into the tour and also reflected the unique commercial and cultural parameters of the performances. Martin and Dennis, as supported by Culture Ireland and the Irish embassy, have often represented Ireland as cultural ambassadors. In a commercial and diplomatic sense, their music, is a high quality cultural brand of Irish-ness. Jameson were very keen to be associated with this brand within their broader remit of promoting Irish culture, particularly Irish drinking culture, within the developing market of India.

Since the early 1990s Irish whiskey has undergone a major resurgence and has for over 20 years been the fastest growing spirit in the world… It is now a popular beverage in India, a country with a great taste for the ‘water of life’. Indian tourists are increasingly finding their way to Ireland, experiencing the folk life through nights of enchanting Irish folk music in the traditional bars. Martin Hayes and Dennis Cahill have together had an important role in taking forward its revival into the 21st century. They are indeed ‘gurus’ of the Irish folk scene and Jameson has been keen to see them come to tour India, they having wowed audiences around the world (Tweedie, 2014).

This corporate sponsorship was devised as 'responsible cultural promotion' of Irish culture as part of the remit of Jameson Whiskey's business model within India. A three page document was created called a 'concept note' which formed the background of any press release or article that mentioned Jameson's sponsorship (See Appendix 2). It was also used as a pitch to the executive board within Pernod Ricard to secure funding.

In supporting this tour of India, Jameson Irish Whiskey are recognising the industry’s corporate responsibility to the bigger picture. This for Jameson is… also by supporting cultural and educational activities in the communities where they operate. Jameson support for the tour of India by Martin Hayes and Dennis Cahill, leading lights of the Irish folk scene, falls into this latter category (from Jameson concept note, Tweedie, 2014)

However, despite Jameson's enthusiasm for involvement in the tour there was one problem. It was discussed that Indian Classical musicians and Indian Classical audiences could take offence at alcohol being associated with the events. It was decided for the sake of etiquette, that Jameson logos would not appear on backdrops, tickets or any official press release. This restriction was then circumnavigated by 'soft' promotion or cultural interest stories through social media and business magazines, websites and newspaper. The promoters further drew connections between drinking culture, particularly that of whiskey, Irish traditional music and the Eastern origins of the Celts.

Hayes and Cahill are renowned across the globe for the excellence of their interpretation of folk music in the modern world. In Ireland, this folk music has been traditionally associated with the ‘water of life’, whiskey. It is believed that it was the Irish religious community, the monks that brought the technique of distilling back to Ireland from their travels to the Mediterranean countries around 1000 CE. For centuries it was the Irish pub that often brought the community together to sing their folk stories, and often the songwriters brought in the place of the ‘water of life’ (Tweedie, 2014)

The connection between music and drinking within Irish culture is a large part of cultural rhetoric. Drinking itself is seen to be an Irish trait (O' Dwyer, 2001, p.199) and the environment of the pub is seen as the natural home of the music. Jameson was cashing in on this association and trying to find a way to justify this to the emergent drinking culture of India.[9] This was highlighted in songs as an example or justification of alcohol being central to Irish culture and was further exemplified in one of our concerts taking place in an Irish 'super pub' in Chennai. A unique Irish-orientalism, somewhat akin to diffusionist Bob Quinn's (2005) Atlantean theory, was at the fore here in the explicit reference to the Eastern origins of distilling in the Mediterranean. This is a similar trope of Irish-orientalism in which musical connections serve as a subversive use of the East as symbol for a noble, ancient and classical culture (Dillane & Noone, 2016). In a further subversive, yet undeniably opportunistic sleight of hand, the Jameson concept note connected the 'monks', 'the music', and the high culture of whiskey. The document stated that, "Celtic music had first come to Ireland around the time of the arrival of the distilling process brought by the monks. Some of its roots are in the music of the East, brought by the Celtic migration that took the music into Europe" (Tweedie, 2014).

In an even more subversive twist, the document suggested that perhaps Irish-Indian connections was not one way traffic, arguing that while the Celts may have brought music to Ireland, "a similar migration took the music into south Asia"(Tweedie, 2014). In this way, an appropriation of my own research and blatant Irish-Orientalism were used as a cultural bridge for marketing the tour. The promoters referred to my own research and the tour, "as an opportunity for people living in India to share this exploration”. The concept note also recapitulated Indo-European linguistic connections describing that there was, "research already indicating the links between Sanskrit and Irish Gaelic (‘Veda’ and the Gaelic ‘Vid’), this further research should show that it is not only the roots of the words that are shared, it is the sounds of the music”. A summary of these concepts was reproduced in the tour Facebook page suggesting. “It’s this music that Jameson Whiskey invites you to enjoy. Clearly, whatever 'this' music could be was already in part defined by the promotional concept of the tour and the re-imagining of Irish-Indian sympathies in a performance context.

The other musicians were perhaps not so acutely aware of the commercial and marketing mechanics on the tour. However, as I was playing multiple roles within the tour (e.g. fundraiser, tour agent, booker, promoter, graphic designer consultant, accommodation and travel logistics and sometime performer) the complicated realities of making the project happen were all too clear. These realities were at times hard to accept and, in the case of the corporate influence, also troubled my conscience. However, out of necessity I had to make peace with this aspect of our inter-cultural exchange and concede that professional music making at this level perhaps always requires compromise and collaboration with larger institutions.

In-between worlds: the mongrel as Third Space

While the promotional, logistical and managerial aspects of the tour became an uneasy part of my performance practice, this was further compounded by the problematic definition of my role within the tour itself. I was neither a manager, producer or tour promoter, although involved in many of these aspects by default. Furthermore, I was neither an Irish traditional nor Indian classical musician. I was the in-between, the cultural conflux, what I describe as the mongrel or what Krebb has called 'an edge walker' an individual who “can discard membership without shedding cultural traits” (in Chang, 2000, p. 23). This ambiguity proved a challenge for booking and promoting shows with promoters in India, as has been discussed earlier. However, without my involvement and my unique multiple “cultural affiliation” (2000, p. 23) arguably the tour would have been unlikely to ever have taken place. The whole concept of the tour, introducing Irish music to an Indian Classical audience, required an intimate performance knowledge of both worlds. Rather than being a hindrance, my multiple marginality proved a great asset as Martin recognised,

the best practitioners in any realm are probably the ones who are 100% devoted to that...[but] there are the marginal figures with feet in different worlds like Dennis [Cahill] for example, Tomas [Bartleet] is like that, and you would be like that... in that same way...it’s a valuable skill area... you can more easily see things that can be brought from one world into the other than I can. That was a very important part of making this functional( Martin Hayes in interview, 2014)).

Another ‘edgewalker’ between Indian music and the West, George Harrison, described himself as a 'conduit' between East and West.[10] While I can empathize with this analogy, I am suggesting that my role was not this smooth. The role of the mongrel is a lot more convoluted. A conduit implies passage between two clearly identified worlds. This binary imagining of culture does not represent the reality of an individual’s experience within multiple cultural frames. In Martin's description of having 'feet in different worlds' we are directed towards the complex multiple sites of knowledge within the somatic world of mongrel musical individuals. I am reminded of the analogy of the Vedic tree of knowledge which roots draw upon different streams of knowledge yet it all feeds the one centre organism (Arapura, 1975). While, within this collaboration, the focus was on two distinct musical cultures, in reality my own practice is more diverse and also draws upon post-rock, free jazz, Buddhist, percussive, and electronic aesthetic paradigms. One aspect of my own practice which I inherited from the Hindustani tradition, namely the reverence and practical deification of the instrument as an entity in itself, also featured as an important connector. “While the major success of the program depended on the brilliant musicianship and experience of Marin and Dennis, on a subtler level, it was also because of the fact Sarode, as an Indian instrument, made a connection between the two music-cultures”(from interview KSS, 2015)

The sarode, acted as an external representation of my own hybridity, it was a “kind of half-way house... that kind of helped bridge us...at least sonically into that world”(Hayes in interview, 2015). Martin also half-jokingly referred to my presence on stage as a trio as a sort of 'calling card' to Indian audiences. “To have you on the stage with a sarode...was also sort of a calling card...kind of a...'Hey, don't be afraid of us...(laughter) Check this out! You know...look...we gotta a sarod!' We're not too strange....you know...look...doesn't it sound a bit Indian? Try? We're curious, we're tolerant … so I mean, it had that as well” (ibid, 2015). My hybrid instrument became a Third Space of musical action between the perceived margins of Irish and Indian music culture. This instrument, which is uniquely designed and made for playing Irish music, was even named after me by one interviewer for Chennai Live FM. "Matthew Noone, who is using what we will now call the Noone Sarod. You heard it first here on Chennai Live, if you ever hear about the Noone sarod again well this is where it started on Chennai Live FM"(from the film Sound of a country). This suggests that, not only individuals, but musical instruments themselves offer a potential site for inter-cultural collaboration. Instruments such as my sarode, represent an “inscription and articulation of culture's hybridity” (Bhabha,2006, p.157) and through performance, culture is ‘resinscribed’ (Derrida, 2004).

Dennis described a similar pattern of an instrument representing a Third Space of enunciation with genre straddling fiddle player Coamhin O' Raghliagh.[11] Dennis actually used the metaphor of a 'gateway' to describe the role of instrumentation in hybrid music. He explained that in making good inter-cultural collaborations that, “there are gateways with it. You know, for instance, Coamhin using a sort of a hybrid hardanger fiddle, is completely different yet it fits the tradition...cause he makes it fit the tradition” (in interview, 2014). An important reflection here, is the way Dennis alludes to the importance of the flexibility to experiment yet still keeping within a tradition. This is an idea that has concerned me for many years in my development as a sarode player performing within and also outside of the Indian Classical tradition. The question of authenticity for me, is not about purism but as Dennis suggests “more about keeping the concepts which make it the tradition, holding it together...and knowing what you're bending” (ibid, 2014). Importantly, as KSS recognised, some musicians have this opportunity more than others, “the young and the bold musicians with giftedness are freer to explore to further their own interests in music” (in interview, 2015). Martin also recognised the important role of individuals who can combine different elements within a tradition are to the musical evolution. He described how,

people with feet in different worlds are an important glue for that... they always have been...even back in the early 70's of Irish music[12]...they were all outside...they were all makers of glue, you know...that could pull different elements in and connect them, you know...So, the marginal transitional figure in Irish music plays a role.

Not only was I translating Irish music onto the sarode but I was also responsible for interpreting Indian music for Martin and Dennis. In my own field notes I describedmy role “as interpreter or wing man for Dennis and Martin and making sure they were in the groove”(FN 2014). In an interview with Martin and I discussed my in-between role.

Matthew: “I was in a funny position of being in-between…

I really felt it when we with Karaikddi, you know...it was like literally you and Dennis on one side and Karaikuddi on the other...and you're in the middle...”

Martin: “Well...I mean...you knew enough of their language

Matthew: “Just enough...”

Martin: “Well, you knew enough to be able to interact with them...and to make it

possible for me and Dennis to even begin to feel comfortable...you know that was part of the game was just finding a comfort level of playing...you were kind of essential there and I realised that we could have had some very awkward moments if you weren't there because you were the only one who could translate both languages. So, you were able to tell Karaikuddi what was happening. You were also able to tell Dennis and myself what was happening...and you also knew where our limitations were....in terms of comprehending that.... just having that dialogue “(in interview, 2015).

Chasing the Squirrel

Chasing the Squirrel, or more accurately Hunting the Squirrel, is a simple jig of English origin which has been subsumed into the repertoire of Irish traditional music.[13] This melody was the final piece in a collaborative performance with South Indian veena player, Professor K. Subramanian after a five day residency in his music institute called Bhraddvani in Chennai, Tamil Nadu. The name of the tune represents a resonant analogy for our quest for inter-cultural musical sympathy. Over the course of our residency, we had an extensive itinerary of interactions, workshops, lectures, cultural tours, media interviews and three scheduled concerts. While we immediately enjoyed and respected each other's music, it took hours of talking, listening, translation, negotiation and compromise to come up with something worthy of putting on a stage for the final performance in the Egmore Museum. Over the course of our residency, and even in the final performance itself, there was a tangible sense of 'chasing' or sometimes more deliberately 'hunting' that evanescent quality that marks a satisfying musical collaboration.

While we had some previous experience in Delhi of working with Indian musicians, this encounter was different as the musicians we worked in Delhi and later in Mumbai were young and well versed in cross-cultural 'jam sessions' as they described them.[14]

The time frame for Chennai collaboration was much longer and the expectation was higher due to the residency and also because the Madras Music Season was underway when we arrived.[15] Martin was acutely aware of the difficulties involved in exploring a collaboration in an in depth way.

it’s actually tricky enough because Indian music has a very very unique structure and kind of set of rules that have evolved and developed over a very very long period of time. And they've got complicated rhythmic patterns and structures, much more complex than ours and also they have a kind of set of rules around scales, and many scales and ascending and descending scales and all that. So, it’s quite complicated (interview, 2015)

However, after our initial collaborations in Delhi, Dennis was upbeat about the sympathies between the two musics, suggesting that, “in an odd way, it’s very similar...the concepts are very similar to Irish music. It’s about phrasing, a bit of improvisation and mainly in the rhythms and the approach...the instrumental approach towards it...there’s rules but they're bendable” (interview, 2014).

On the very first night of our stay in Chennai, we were introduced to some of the complicated 'rules' of the Indian tradition by our host Karaikuddi S. Subramanian and began the process of discovering which, if any, were 'bendable'.[16] The professor talked to us for a long time about the spiritual nature of sound and Indian music philosophy. From the beginning of our initial communications to organise the tour, the Professor espoused the spiritual nature of music as the gateway for our collaboration and this was manifested in a spiritual text which he had sent to me (Appendix 3). He performed for us some pieces which he thought could serve as the basis for our collaboration, weaving together the spiritual text in Sanskrit with three different ragas which co-related to the bava (mood) of each text. Despite the undeniable beauty of the pieces, it was hard even for me, to latch onto any repetitive melody or familiar scale structure as the renditions, which were still short by Indian standards, took at least 30 minutes. I wondered how we were going to make this collaboration work and I realised that there would be a need for some serious simplification and translation of these ideas into something approachable from an Irish traditional music perspective.

Martin described his own feelings in a personal interview after the tour, explaining that “it sounded like at first with Karaikuddi we were heading for a world of dense complexity and I was just like thinking, 'Oh my God....I'm going to be exhausted by the time I get out of Chennai because i don't know if I can digest all of this stuff in one go” (interview, 2015). Despite my own love and rudimentary knowledge of both musics, it was hard not to notice the polarity in the two musical approaches from the first evening’s examples. How could we begin to make a collaboration which went deeper than a 'jam session' when the three fundamentals of the two musics (melody, rhythm and improvisation) seemed entirely at odds with each other?

Irish-Indian Sympathies and Divergences: Melody

McNeill states that, “the most immediate thing that confronts performers involved in cross-cultural collaborations, is the degree of difference that is felt between their respective musics” (2007, p.7). Dennis contemplated that although the two musics were quite different, it was only a matter of scale, stating that, “the similarities are in the concentration of the rhythm and the melody. What's different is the scale of the rhythm [and] Indian scales are larger”(interview, 2014).

Undoubtedly, Indian melody operates on a much grander scale than Irish traditional melodies. Yet the difficulties that we encountered were not just a matter of volume of material but, an fundamental understanding of these basic building blocks of performance. Utsav Lal, who has experience with both Hindustani and Irish traditional music described that, “the whole base of the music is slightly different” (in interview, 2014).[17] As Utsav suggests, in particular the melodic basis of the musics are quite different. From that very first evening of interactions in the Professor's office, it became apparent that we had very different perspectives on what actually even constituted a melody. Martin tried to find some comparison between Irish melody and the melodic structure of rag. He described that, Irish music was:

basically centred around melody which is a little bit akin to the rag here but it's not quite the same. The rag is like a set of instructions to work with, in some ways, but our melody is quite specific....They have a capacity to kind of slowly evolve and develop or the more you can repeat the melody without changing and then at a certain point when you do make a change it becomes more significant. So, it's a subtle movement in the melody but it's melodically based (in interview, 2015).

The melodic basis of Irish music was much harder for the Indian musicians to grasp then we initially imagined. We spent considerable time in Chennai exploring Irish melodies as an ensemble, both jigs and reels, particularly in the key of D minor which were more suited to my sarode and also worked with the veena tuning. Yet they proved elusive to master. Martin described his surprise when he says,

I think it was quite difficult for them to just comprehend the tune. Which was kind of a shocking thing for me to realise...like, it took me a while to realise that they weren't really hearing this as I had saw...I thought Irish music was so simple. I thought it was one of the simplest forms in the world and anybody could just...grasp it immediately (in interview, 2015).

Likewise, Martin and Dennis found it difficult to pick up an Indian composition. In fact, throughout the entire tour, we only performed one Indian composition as an ensemble, a melody based on Rag Dhani. [18] This was in fact, what I believed, a fairly simple composition that I had begun teaching to Martin prior to our tour. The lack of fixed, short, and readily identifiable melodies in Indian Classical music made our collaboration process more difficult. Despite watching concerts and having melodies broken and down and explained to us, by day three of our interactions with the Professor, we had actually produced very little evidence of material for a collaborative performance and had not actually decided on what compositions or melodies we would play as an ensemble.

Martin Stokes, although working with Irish and Turkish musicians, has an astute observation as to the reason for this difficulty in melodic sympathy. He describes how, “the intervallic and modal structure of [Turkish] music revolves around small groups of tones and non-tempered intervals, whereas that of Irish music is equally tempered, rapidly performed and covers a wider range" (Stokes, 1994, p. 110). A similar generalized comparison could be made between Irish and Indian music.

For our final performance as an ensemble in the Egmore, I facilitated a necessary process of distilling all the suggested melodies and compositions until we arrived at simple pieces that we could all understand. The Carnatic gat was in a pentatonic scale and matched somewhat the simple D minor reel The West Clare Reel. Martin described this performance decision as, “we can find the simpler melodies that give them the freedom to float on top and interact with solos if they wish, you know” (in interview, 2015). This was more or less the template for all of the ensemble performances with Indian musicians on the tour, simple Irish melodies, either jigs or reels in D minor, with small inclusions of Indian melodies.

While we did engage with a Carnatic composition in our performance in the Egmore museum in Chennai, we did not even begin to learn the movement of the raga and only really caught a small refrain of the actual composition as it proved too difficult to learn in the short time provided. Martin described his experience trying to learn Carnatic music as 'mind boggling'.

These ascending and descending scales that are both different is just like . . . just kind of a mind boggling idea for me, you know. (laughs) And coupled with some big complex rhythm pattern, you know. I’m going, oh my god, like I don’t know how they can internalize that at all and it’s hard for me to see where the connections are (in interview, 2015).

Repeatedly, my role was to find where the connections where even when the other musicians could not see them. However, the difference between Irish and Indian melodic structures seemed at first to be an impassable obstacle. Martin described how, “As soon as you begin to examine it, they look like an impossible combination to actually put together because…because like…the melody almost doesn’t exist in Indian music as we know it... and in Irish music there really only is the melody, if the truth be known” (in interview, 2015). Despite Martin's description, which is in one sense correct, arguably Indian music is all about melody. As Wade explains this, the use of alap (the unmetered introduction to raga performance) asserts the “primacy of melody in the hierarchy of music elements in the Hindustani tradition” (2009, p.141).

This divergent approach to melody was not just a problem between the Irish and Indian musicians. Within the genre of Indian music there is also a very big difference between Hindustani and Carnatic approach to melody. For example, when I began to work with the Professor on raga for a possible classical collaboration, it became clear that even though we took the same rag (Rag Kirwani) which is from the Carnatic tradition originally, we had very divergent techniques and melodic phrases. I finally suggested that we drop this piece as I could see that it wasn't going to work and that we focus on finding an Irish melody that could work in sympathy with one of the Professors raga based compositions. A divergence of melodic understanding is not necessarily a cross-cultural phenomenon but also is a difficulty within the same genre.

Ultimately, the resolution of melodic difference in musical collaborations depends on the experience and mode of operation of the individual musicians involved. On this tour, the presence of my mongrelity was a essential factor in helping to establish melodies that would be digestible to the various musicians. Likewise, Martin was also quite good at realizing which melodies might work from the Irish tradition as he has many years’ experience working with musicians from various cultures and traditions.[19] However, this process often meant finding simpler melodies that could be most easily learnt in a short space of time, and even then, it didn't always necessarily work. This is because melodies are much more than a simple combination of sequenced pitches in time. Melodies serve different functions in different musical traditions and have different intrinsic rhythmic structures designed to realize differing musical intentions.

Irish-Indian sympathies and divergences: rhythm

Perhaps the most notable degree of difference and difficulties in exploring Irish-Indian melody is rhythmic rather than melodic. North Indian rhythmic structure or tala, unlike in Irish music, is not strictly tied to the melody. Irish traditional music is perhaps inherently rhythmic. Martin stated that, while “Irish music at its core, has a depth of melody, it is rhythmic in interpretation” (in interview, 2014). The Professor also interpreted Irish music in a similar way. He articulated that Irish melody is infused with rhythmic pulse, what he an “intrinsic rhythm which effortlessly blend[s] with the melodies” (in email communication, 2015). In contrast, the tala, both in North Indian classical music, is designed to offer a cyclical space for improvisation and is not for dance, 'lift' or groove.

While Irish scholars, such as Ó Súilleabháin (1990) and O' Ríada (1982), have argued for the primacy of cycles in both Indian and Irish music forms, the form and fundamental nature of these cycles are completely different. Indian classical music is framed in cyclical patterns which range from a 3 beat up to a 128 beat cycle and all sorts of wonderful deviations in between. These cycles, unlike the rhythms of Irish music, are not related to the melody as such and offer a continuous framework for extended melodic improvisation. Whereas, while one could argue that Irish music is intrinsically melodically based, its rhythms are inherently built into the tunes. These fundamental differences of rhythm provided understandable difficulties in our collaborations. Martin confessed that, “Dennis and myself were completely bamboozled by the counting that was going on.... I realised no matter how gracious they were in showing you...I knew that this was not going to be two days’ work. This is like two years’ work” (in interview, 2015).[20]

Indeed, I was also encountering difficulties with the Indian compositions that KSS was attempting to teach us as they were Carnatic in structure, which rhythmically differs significantly from my experience with North Indian music. On day three of our residency I suggested that we work on a classical piece to perform together as a sort of North & South Indian collaboration and also as a way to get more comfortable with the material he wished to work on with Martin and Dennis. It took a great deal of “noodling” as I described it in my field notes. Even after settling on a raga which I was familiar with and also was common to both traditions, it took over an hour before KSS and I managed to even find some common ground in approaches to improvisation. I found that we had different rhythmic phrasings and constructs of melody.[21] It was hard to discern whether this was stylistic or matter of repertoire and lineage.

I began to feel that a percussionist would greatly help with the collaboration as our initial interactions had been limited to working with melodic passages and exercises with a lot of theory but not concrete melody or structure. It had been very difficult for Martin and Dennis to catch any repetitive motive in KSS's ideas and I sensed that percussion could at least add a 'groove' that Martin and Dennis could work off. At this stage, serendipitously, the Professor's 'uncle', Karaikuddi Krishnamurthy, who is a world renowned mridangam player, called into the office in Bhraddvani. We discussed the idea of him joining us for the performance. I became greatly relieved at this inclusion as, despite Irish music being melodically based, I knew that Martin and Dennis would not grasp Indian melody in the short time provided. I hoped that through the primacy of rhythm that we might find a clearer synergy.

However, the inclusion of Indian percussion, especially in working with Irish melody also proved problematic. As Martin candidly stated, in reference to both the percussionists that we worked with, that “it was kind of hard to tell what they were doing...they weren't hearing this A part of the tune and this rotation at all. They were looking for different measurements. They wanted to measure the whole thing over say, five rotations of a jig and literally count that, I think” (in interview, 2015). [22] What the percussionists were in fact most likely doing was using Indian rhythmic cycles which are much longer than the 8 bars -16 bars of a traditional tune. Likewise, the mridangam and tabla players sometimes chose to use shorter, more folk orientated rhythms which did not clearly synchronise with the different parts of the Irish melody. In particular, this was evident in our first collaboration in Delhi and it caused some amount of friction in rehearsal and the performance. As Martin described, “It was a little contrary thing, especially for the percussionist. Who suddenly...I think everything...previously was...was...counted in its structure and they didn't have to analyse the notes of the scale but I was asking them to kind of hear the melody of the jig repeating….that was not registering at all” (in interview, 2015). Indeed, the tabla player in the Delhi collaboration told me candidly backstage that Irish music was boring and that every tune sounded the same, which became a justification for his lengthy unplanned solo improvisations.

This disjuncture in rhythmic approach was also apparent in our excursions into Indian classical repertoire, in both our collaborations. As mentioned previously, in Delhi we performed one Indian classical compositions based on Raga Dhani. It seemed that the main difficulty was not the melody but the rhythmic structure of the melody. The composition was divided in a twelve beat cycle called, ektal. But the division of those twelve beats is 2,2,2,2, it was not 6 or 12 or three or even a groove of four which was troubling for Dennis.[23] Dennis explained in an interview for the Chennai times that he understood before the tour that rhythmically the Indian experience was going to be a challenge. As an accompanist, Dennis has often described how he takes his inspiration in Irish music from dancers. Naturally, before coming to India, Dennis began to listen to tabla players however, this proved a humbling experience.

I listened to various..various players before getting here so that before we could some of this I could understand exactly how much I don't know...and avoid doing that. It's veryinteresting. It's a whole different approach to music. It takes a lot of getting used to...playing lots and listening lots” (in Chennai times, 2014).

In our performance in the Egmore museum, the difficulties of finding rhythmic sympathies were highlighted when we played a Carnatic piece which involved some structures for improvising. Martin and Dennis relied heavily on my verbal cues to keep in time with this piece. The following extended excerpt from my field notes illustrates the performative manifestation of the rhythmic divergences between the two musics.

the mridangam plays a tihai[24] which Martin and Dennis cannot recognize, which is the cue for us to join in the next section of the raga. I start to tap my foot and through visual cues, let Martin and Dennis know that our mukra[25] or riff is approaching. KSS continues to play a relatively fixed composition over the rhythm while we catch a short mukra at the end...Martin and Dennis had not fully internalised the rhythm cycle and had found it difficult to identify the sthyai[26] and antara[27] sections of the composition...So, my job was to keep track of the composition and also the give clues for the mukra...at times I felt not really in the music as I was keeping half of my awareness on whether Martin and Dennis were catching the mukra at the right time and also where KSS was in his improvisation...”

It is a testament to Martin's respect for Indian music and also his intuitive approach to performance that he did not try to launch into an Indian style improvisation or give any pretence that he had mastered Indian rhythmic cycles in the short time available to us. It also points to the somewhat intellectual nature of Indian music, particularly for a percussionist. This intellectual and mathematical approach to rhythm is, in many ways, the antithesis of the lineage of Irish music to which Martin is connected. In my questions around this difficulty with rhythms, Martin suggested that,

you have to distinguish me from the rest of Irish musicians in respect to this cause like (laughs) because like, it had been quite common for Irish musicians, for example, to play difficult time signatures or untypical ones for example like Bulgarian rhythms or you know Serbian...you know from that part of the world...so some musicians are good at getting comfortable with that. So, I'm probably not equipped as well as some younger musician now might be to do that. I'm equipped more like Junior Crehan going to India almost, you know. I have a little more capacity to merge into things or twist thing around, you know, I can be free with it but like, I can only let my body be free in the rhythms that I know (interview, 2015).

However, I am not suggesting that we should understand this divergence of rhythm through a hierarchy of complexity, with Indian music necessarily trumping all other music. Western musicologists have been complicit in perpetuating the 'otherness' of Indian music through espousing it as a pinnacle of complexity in musical terms, a phenomenon articulated by Jairazbhoy (2008) as “Indo-Occidentalism”. This has contributed to a continuation of the folk-classical divide where what is deemed a simpler music form is deemed inferior. Certainly, at face value Indian rhythmic structures are much more complex and varied that Irish rhythmic accompaniment. Yet when one considers the inherent interweaving of melody and rhythm in traditional tunes, the process of Irish music becomes equally as complex and elusive to explain. Martin ponders that, “I think we digest melodies in the same way. Like, they have a big array of rhythmic structures and scale structures, which are the rags I suppose and...so they digest that and make that second nature. So they digest that and make that second nature. We have to digest all these melodies and make them second nature”(in interview, 2015). The melodies to which Martin refers to, while not explicitly so, are inherently rhythmic. It is only from a lengthy digestion process that Irish traditional musicians are able to fully explore the expressive capabilities of what appears to be a very 'simple' form. Naturally, it would seem almost impossible, for any musician who is mainly absorbed in one form, to become fluent and completely comfortable with a different tradition in such a short period of time as allowed on this tour.

While perhaps rhythmically the collaborations were not all they could have been, at the same time, they worked musically and, mostly, held together on the stage. However, it is undeniable that the rhythmic elements of both traditions were expressed in their simplest structures to make this work. For this reason, we chose tune types from the Irish tradition which were relatively simple in rhythmic complexity (simple jigs and minor key reels) and we stuck with standard Indian talas within permutations of 3 and 4 (sitar khani, teental, ektal). The full extent of the rhythmic possibilities of Irish-Indian musicking would take considerable sustained effort on a much smaller scale than the tour provided to reap any real benefits. Moreover, an engagement in a more nuanced manner is crucial in regards to extending the key musical expressive element which underpins the rhythmic aesthetic of both traditions, namely improvisation.

Irish-Indian Sympathies and Divergences: Improvisation

Mc Neil states, that the concept of, “improvisation is widely recognised as the central and defining element in Hindustani classical music” (McNeil, 2007, p.4). Likewise, whilst a considerable portion of Carnatic music consists of music that has been composed, the true challenge for the musician lies in aspects of improvisation. For the discerning audience too, the improvised aspects like raga alapana, neraval and kalpana swara reveal the talent and skill of the performing artists. In fact, improvisation could be considered the soul of Indian classical music. While many western musicians, particularly those from a jazz background, have been drawn to Indian music because of its scope for improvisation and expression, at the same time Indian Classical music is incredibly structured and systematic. Holryde argues that Indian, “improvisation has not, however, the same connotations as those with which we invest in the word in relation to jazz” (1964, p. 151). While general rhetoric on Indian music, suggests that 80% of the music is improvised, more accurately it involves a recapitulation and exploration of learnt material from decades of intensive study with a master. Wade asserts that it is important to acknowledge that improvisation, within any musical system, does not mean “completely free” or imply that music is newly created in performance without being based on anything pre-existing (2009, p. 134).

Irish traditional music also has a strong rhetoric of looseness in interpretation and scope for the individual to improvise. Iconic fiddler, Tommy Peoples describes it thus, "Traditional music is composed as you go...The performance is the composition, like with painting. It's not untouchable on paper, it's [created] as the performer feels, as the mood dictates, on the day. He paints his picture every time he or she performs" (in Shortfall, 2014). Yet, McNeil cautions that, “while improvisation is common to most musical systems around the world, it does not necessarily follow that it is understood and practiced in the same way” (2007, p.4). Indian pianist, Utsav Lal, who has experience as a performer of Irish and Indian music as well as jazz, explained that while, “both Indian and Irish music are very organic” (in interview, 2014) and a share a sentiment of improvisation, structurally they are very different.

After our collaborations in Mumbai, Utsav while generally an optimist in terms of Irish-Indian musical sympathies, conceded that there was a significant difference between the approaches of improvisation. He stated that, “Irish traditional music doesn't have like alap...although the way you pause and the phrasing sound similar to alap...it’s a dance form of music. It’s kind of for entertainment...it’s a folk music, it’s for expressing things that relate to people” (ibid, 2014). Furthermore, when asked to discuss any similarities, he compared approaches to improvisation as, “playing the same tune, but in a slightly different way” (ibid, 2014). However, I would argue that playing the tune in a slightly different way each time is definitely not, to paraphrase Seán O' Ríada, ‘just the same as Indian Rag’.

Martin conceded that, “Irish music is not improvisational music, performed in that sense, it's not the core element of it...improvisation is the core element of jazz...the core element of Irish music is still the melody (in interview, 2015). While Martin Hayes has become renowned as one of Irish traditional music's great innovators and improvisers, his concept of improvisation refers to stretching notes, phrases, timings and intonation within the limitations of traditional melody. The way in which Martin and Dennis arrange their extended medleys of tunes are also often improvised, something akin to the performance practice of a traditional session, but also following a similar sonic template to the dynamics of raga development.

A radio interviewer in Chennai also drew an analogy with Indian music when he heard Martin's description of his approach to traditional melody, “So, there's this basic frame work on which you build which lends itself to moving away from it and coming back to it, and away from it and coming back to it” (Kapur, 2014).

However, improvisation in Indian music is much more than dynamic builds or bending or stretching a note from a fixed melody. Mc Cormick, in a review of Martin and Dennis's album Live in Seattle, drew comparisons with Indian music but was careful to highlight that, “The problem is that Irish music doesn’t work like the music of India...The melodies are too formulaic. The idiom is structurally and rhythmically too circumscribed by its function as dance music to afford the musician much room for improvisation” (McCormick, 1999).

Improvising successfully within any musical tradition requires an accumulation, absorption and embodiment of complex knowledge within a specific cultural milieu. Martin refers to this quality as embeddedness, the ability to inhabit the music so that liberties can be taken, a quality that takes considerable time to achieve.

Until the melody is something that is singing out of your innermost being without any intellectual interference, until that moment, you don't have the freedom to stretch a note. Or at least, you won't have the freedom to stretch a note in a meaningful way or even to know the right note to stretch. Not until it’s just embedded within you can you have that experience” (in interview, 2015).

This kind of habitus was just as unlikely to be acquired by the Indian musicians within the short space of our collaboration as it would be for Martin, “It seemed unlikely that I was going to get to that level of embeddedness of the structure of Indian music in that period of time. Neither were they going to an Irish tune embedded either. I thought that might have been easier, you know”(in interview, 2014). Somewhat sympathetically to the difficulties of this collaboration, Mc Neill argues that, “attempts to apply an Indian template” to other music ultimately misses the point. He suggests that in doing so, “the tendency is for only those things that are meaningful to that template to end up being recognised, while things which are not recognised by the template remain only partially audible to it or are missed altogether” (2007, p. 5). Our collaborations both with KSS and with the musicians in Delhi/ Mumbai, did not really attempt to apply an Indian template to an Irish structure but rather the two existed side by side and sometimes overlapped. However, in the course of a performance a much larger proportion of improvisation was given to the Indian musicians, myself included, in accordance with an understanding that this was primary within their system.

Both rhythmically and melodically, while opportunity was given for improvisation in our collaborations, this was mediated by the constraints of Irish melody and rhythm. As Martin stated,

the tabla rhythm can actually work so long as they’re not adhering to their normal structures. You know, the flute can actually do a bit of modal improvisation over a simple melody. So, we can sort of be connected that way but they have to abandon a lot of what they do (in interview, 2015).

This 'abandoning a lot of what they do' was likewise necessary to find simpler melodies from the Irish tradition to which some kind of improvisation could be applied. Mc Neill, offers a critique of this approach suggesting that “in a cross-cultural context it is important that any discourse on improvisation should not be limited by ideas in any one musicological system, and certainly not by one in which it is largely a subordinate practice” (2007, p.5). The discourse of improvisation in this collaboration was not completely limited to the system of Irish music, in which indeed improvisation is more of a subordinate practice, yet it was definitely the main template. However, substantial freedom was given for the Indian musicians, including myself, to improvise was to how they saw fit, often drawing upon raga structures from matching scale types. For example, in Delhi, Paras Nath discussed with me how he would use Rag Bhimpalashi in his solos while Martin and Dennis grooved away on a reel in D minor (Broken Pledge). KSS discussed several matching Carnatic ragas to the scale of another D minor reel (West Clare Reel).

The discourse on improvisation in these collaborations was in a subtle yet significant way, facilitated by my own liminal position between the two traditions. Often I would be discussing the raga or thata type with the Indian musicians and also explore possible tunes that might work in that mode with Martin and Dennis. This type of discourse is in itself a social linguistic improvisation which is crucial in developing inter-cultural music exchange. Mc Neill has likened the success of musical improvisations as a good musical conversation (2007, p. 6-9). As others have explored inter-cultural musical exchange is a field of negotiations of power, articulation and interpretation of knowledge through varied conversational styles of culturally bound individuals (Stokes, 1994; Wilkson, 2011).

Yet ultimately, there are intrinsic limitations to this type of analysis. Even though we are focussing on the performative moment, we are still measuring music in terms of external manifestations as a product something that justifies the collaboration taking place. I would argue that we should be less focussed on the sonic output of these musical collaborations but what is happening within the musical performance and the musicians themselves. This could be described as the somatic 'inner fusion' of inter-cultural music exchange. Musicking is intrinsically rewarding in one's inner world. The activity of making music is not necessarily just about final output. In this regard, the 'conversation' analogy limits our discussion on the important inner workings of this music on the musicians and the listeners. I am more interested in what takes place in improvisation within the musicians themselves, a phenomenological understanding of this kind of musical Being-in-the-world. I include below an excerpt of my field notes from our final performance in Chennai. I use this field note as it relates to improvisation as it focusses on the complex sets on knowledge and emotion involved in musicking. In particular, it outlines some of the unique challenges of moving between improvisational forms.

When it came time for my improvisation within the Carnatic section, it felt like I was being released from the restraints of all these roles and I let loose. Despite being on short passages, I felt I was able to express the combination of emotion which I embodied at that time- a muted frustration, reaction to judgement, desire to connect with feeling and something divine or outside the self. There was also the great freedom that the form of Indian Classical music allows in expression. Despite not being particularly familiar with the rag, I followed the rules as best I could by focussing on more rhythmic passages. I felt particularly encouraged by Krishnamurthy who had praised my playing in rehearsal the previous day and had also bought me a doti to wear for the concert. Every time I looked over to him, he would make eye contact, smile or nod his head in encouragement. He also responded with 'Shabash![28]' after some of my improvisations.

I still vividly recall this performative moment many months after the event. We had begun our final piece with lengthy improvisation by the veena which led into a fixed bandish or short refrain which myself, Martin and Dennis followed. This required verbal cues from myself to let Dennis and Martin know when the 'hook' or mukhra was coming so that we could land on the right beat. I felt very conscious of my teacher being in the audience and also the discerning ears of the Chennai listening public. I was given passages for improvisation in between the veena and felt liberated in that performative moment to give vent to my various emotions. Staying within the melodic and rhythmic structure as best I could, I closed my eyes and let loose, focussing on the experience of the moment. The performance wasn't a disaster by anyone's measurement, quite the opposite, as we received standing ovations. However, I felt unsatisfied with the lack of integration in the music, especially on the responsibility of my role in understanding what was happening in both traditions.

A European composer who had spent many years in Chennai studying Carnatic music candidly told me afterwards that, “You were the only one on stage who knew what was going on”(FN 16/12/14)). In a sense, this comment was true, as I was the only who could mediate between the two forms, although I was by no means a master of either. This improvisation was fraught with cross-cultural complexity and externally as a 'conversation' was somewhat limited, yet from my own internal experience it was a rich and cathartic experience although perhaps not musically the most satisfying. How is it then that a musical collaboration, which while on the surface appeared to be working in technically oppositional directions, satisfied the audience members and to some degree the musicians involved? Perhaps the sympathy of the collaboration had less to do with musical tangibles and more to do with the more intangible world of feeling.

Cry now/Laugh now- Irish music and affect

While it may be seductive to conclude that inter-cultural music collaborations work because, as one radio presenter concluded in Chennai, “ultimately it’s all coming from the heart” (Kapur, 2014) a critical perspective is also pertinent. Both Irish and Indian music have a historical rhetoric of strong emotional efficacy. While Indian classical music has a long history of being intrinsically linked to emotional affect, which shall be explored in more detail later, Irish traditional music has an equally complex yet perhaps more ambiguous relationship with the world of feeling. Smyth has asserted that there is a “close association between certain aspects of Irish music-certain rhythms, instruments, keys, tempos, melodies, traditions-and certain emotional responses” (2008p. 51). This is further connected to “widespread, linked notions of the Irish as both extraordinarily musical and extraordinarily emotional” (2008, p. 59). Smyth has likened the predominant models of Irish musical affect to two categories, Paddy Sad & Paddy Mad...one signifying “dispossession and defeat” and the other “pleasure and excess as a qausi-religious response to the disappointment of everyday reality” (2008, p. 52).

This simplistic dichotomy of Irish musical affect seemed to strongly resonate with both musicians and audiences on the Indian tour. Indeed, two of the main organisers of the Chennai leg of the tour described the emotional responses to Irish traditional music that they experienced on the tour in strikingly similar terms to Smyth's 'Sad/Mad' axiom. They stated that the music was emotionally charged, "it’s moving. Everybody that hears Martin, Dennis and Matthew playing here....They get it. They get it. Even from the audience. Lay people. They just sit there. Just hooked in. This is something you can enjoy. Cry now/ Laugh now” (from Sound of a Country, 2014).

The idea that Irish traditional music is generally 'happy' music is one that seems to dominate general popular perceptions. The professor described Irish melodies as having a, “the directness of appeal of the songs to the inner joy which is part of everyone. Everyone, on hearing you all were joyous. As if there is no need for explanations of sorts. Instantly the listener seems to own them as their own. that they enter the mind and the body of the listeners ticking the heart to ecstasy in sympathy” Furthermore, he describes the strong affect of the tune 'Chasing the Squirrel', “When I taught the song "Chasing he Squirrel' to our children, they all throbbed with happiness” (in email communication, 2015). In our radio performances in Chennai, the presenter was visibly overwhelmed with positive emotions with the pieces we played as a trio (the jig Sheep in the Boat and a reel Toss the Feathers). He responded that, “It's a very, very happy music. It almost like grabs and tells you get there. Be there. Your attention is already grabbed". After our rendition of Toss the feathers, he responded, “ I'm just about sort of getting out of my chair and dancing to this....I have goose pimples”(Kapur, 2014). Furthermore, this emotional affect was very much linked to an imagined landscape of Ireland. “Wow, in the moment when you hear that music it’s almost like you are walking on those lush green fields somewhere or you're sitting in a pub somewhere and people are sitting there, happy”(ibid).[29]

The relationship between affect and music is a complex one and “remains stubbornly ungeneralizable” (Thomson & Biddle, 2013, p. 6). While we may all agree that music affects us, the state of this affect is not universal and is heavily influenced by context. Music affects us in different ways depending on our cultural and musical experience. Storr asserts music generates a “general state of arousal rather than specific emotion” (1992, p. 30). This “emotional arousal is partly non-specific” (1992, p.71) and arguably our specific emotional cues are primarily culturally determined. This leaves the musical moment open to affective interpretation, which is in turn conditioned by cultural experience. As Blacking asserts, [m]usic cannot express anything extramusical unless the experience to which it refers already exists in the mind of the listener…unless they are already socially and culturally disposed to act” (1995, p. 35-36).

In the examples just given, the joyous emotions which the presenter expressed did not match those of the performers, nor arguably the actual intended emotional affect of the music. Both of the tunes we played were in a D minor setting. Generally this mode would be associated with a more melancholy strain of traditional music. Contrastingly, the radio presenter when he heard these tunes simply imagined people sitting happy in a pub. After our performance, Martin gently described the actual original meaning of the melody saying that “it's actually a sad story about some people on a boat travelling out to the Aran Islands on the West and their bringing some animals and a sheep put its foot down through the boat and they were lost. So, it’s a sad story. The presenter responded, “That’s interesting. So the music is kind of great. It’s nice but it’s a sad song. Is this like something you would sing around a bonfire and tell a story about?”(in interview 2014). There was an awkward silence. This interaction reflects the theories of Turino who states that affective interpretation is “dependent on social frames” and culturally framed expectations(1999, p.237).[30]

While traditional musicians in Ireland may describe the qualities of “exile in the music” (Vallely & Piggot, 1998, p.66) or a quality which is a “characteristically plaintive character, melancholy and [with] an undercurrent of tenderness (Smyth, 2008, p. 176), the reality is that general perceptions of traditional music are in fact very different. For many casual listeners of Irish traditional music, the tunes are basically happy and the slow airs are basically sad. David Byrne has suggested that perhaps this incongruency in emotional intention and its resultant affect may be because, “rhythms override the melancholy melodies” (2012, p. 340).

Perhaps we can argue that certainly Irish music does have a strong affective impact, but the categorisation of that affect is much more difficult to ascertain. In Irish traditional music, the feeling one gets from the music is ultimately dependent on the experience and expectation of the listener. The ambiguity of affect is complicated further by what Massumi would describe as a “crossing of the semantic wires [where] sadness is pleasant…when asked to signify itself it can only do so in a paradox” (2002, p.24). Smyth argues that, “traditional music...exposes the illusion of ideal emotional associations operating instead on an imaginary borderline where sadness and happiness segue imperceptibly into one another” (2008, p55).

The affect of an imperceptible merging of emotion has been described in East Clare music as the “Lonesome touch” or "high lonesome” (O' Shea, 2008, p. 70-74). [31] A musician who has the ability to create this affect might described as having great draoicht (literally magic, a spell or enchantment) in their music. The term is sometimes used to “convey a sense of carrying away...a sufficive heart-felt pain evoked by the music” (Vallely, 2013, p. 222). The term is often used to describe the style of older players and also is associated with a “calm and relaxed personality and [a] peaceful attitude to life” (Crotty in Crehan, 2006, p. 3).

Musically, the feeling of draoicht or the lonesome touch may relate to tonal material, such as the use of minor keys, but is more often related to non-tempered tuning, micro-rolling, the sliding notes (particularly sliding into C and F naturals, and a relaxed tempo “allowing the tune to lead the playing rather than the player driving the melody” (Vallely, 2013, p.222). Other terms to describe the intangible affect of traditional music performance include the concept of nea, nyaah or nyach. The concept of nea is arguably more connected to the vocal (sean-nós) rather than instrumental tradition and in particular is often associated with “the audible manifestation…of a slightly nasal hum at the very beginning and sometimes at the end of phrases…[a] resonant quality produced in the head of the singer, using the bones of the skull and jaw as resonating bodies” (Williams, 2004, p. 134). It also has a resonance with the evocative sounds of the drones of pipes. The great sean-nós singer Joe Heaney described the nea as “the sound of a thousand Irish pipers through history” (in Williams, 2004, p. 134). However, the nea also has extra-musical associations that “go well beyond mere droning or nasalization into the realm of culturally recognised qualities like ‘soul’ in African-American musics or bhava in India” (Cowdery, 1990, p. 39).

While these descriptions are still quite vague, they are perhaps the most explicit definition possible to describe affective theory in the practice of Irish traditional music. While the variety of the above terms may only occasionally be “spoken of by Irish musicians” we must consider the possibility that they represent an attempt to describe not just a basic element of traditional style but “perhaps even the basic element, the ultimate feature by which someone in the tradition can recognize their own” (Cowdery, 1990, p. 39).[32] The performative manifestations of these concepts shall be explored in more detail in the fourth chapter which relates to the final performance.

Irish and Indian modalities